The Community Lifecycle: From Launch to Legacy

Every time someone emails Discourse support asking to extend the free trial on one of our hosting plans because “14 days isn’t long enough for the community to take off”, a tiny part of me dies.

A decade ago, community builders recognised that 6 months probably wasn’t long enough for the community to take off and they were ok with that. They understood that community building is a long game and the play starts well before launch. In today’s world dominated by social media and Discord, people are losing the art of true community building in favour of amassing followers. This miscategorisation of an audience as a community doesn’t take into account how complex the social systems underlying online communities are.

Serious community builders know that communities are ecosystems; they have a lifecycle that needs adaptive strategies.

That lifecycle stretches from Inception – which begins well before the free platform trial stage – and continues all the way through to Mitosis, which is what ultimately happens to healthy communities that enjoy longevity.

Not all communities will reach this final stage, but an example of one that has is the first community I ever joined and subsequently went on to manage – The SitePoint Forums. Although it’s been over a decade since I left, I have a deep and lasting connection with that community, which is still thriving today. As well as providing the support I needed to learn the skills to pivot into a new career, it offered lasting personal friendships, a strong professional network, and a long-standing customer.

How is that legacy created?

Stage 1: Inception

Inception, sometimes known as Genesis, begins when a brand/individual/organisation that is engaged with their target audience recognises that they have a collective need that might be met by a community. The nature of the audience doesn’t matter; successful communities don’t just serve business goals, they solve a very real problem for members – why else would they invest their time? The cold start challenge of scrambling to get those first crucial members is only the experience of those that launch before they properly strategise.

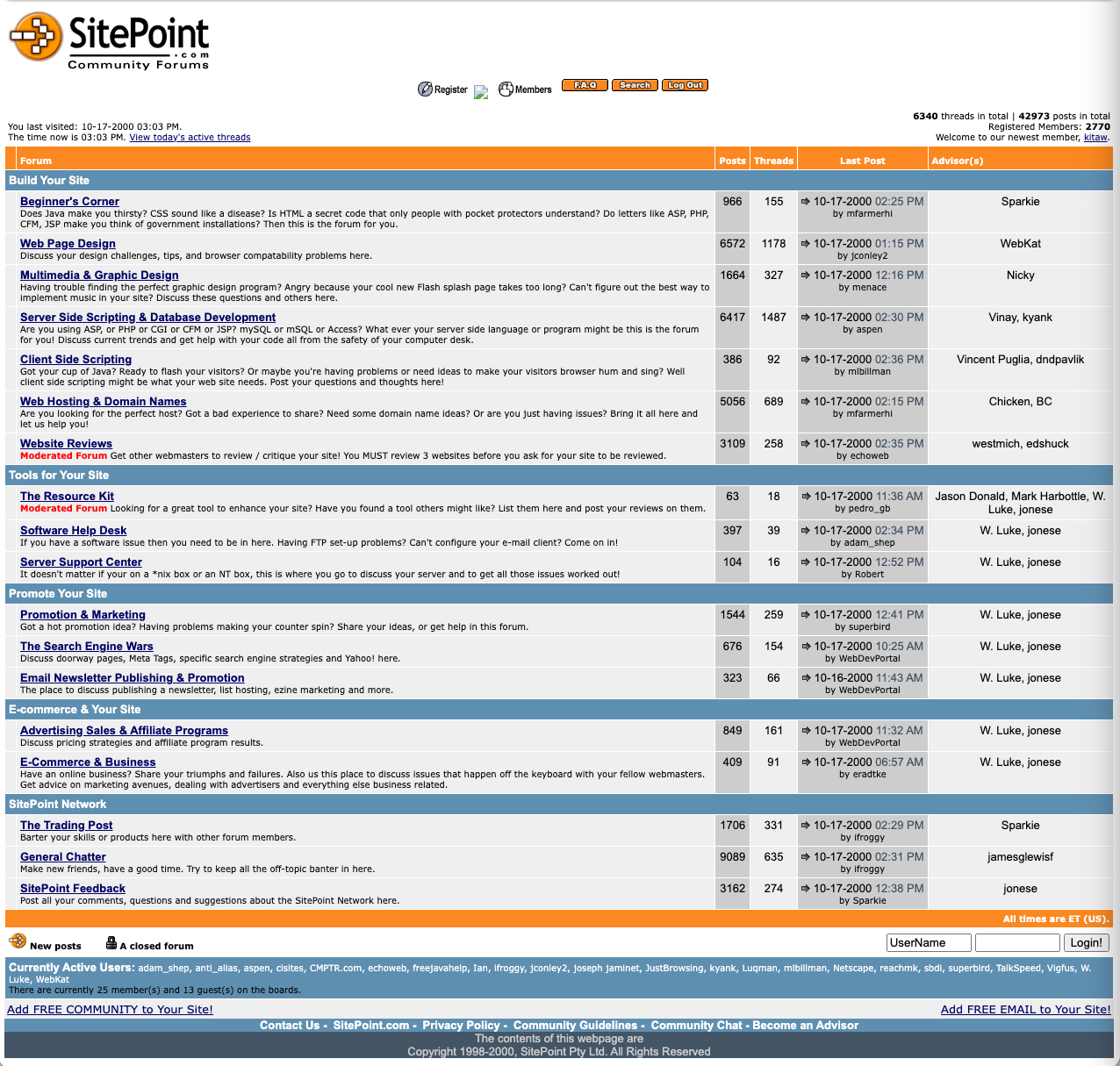

It was 1998 when SitePoint co-founder Matt Mickiewicz first began engaging with his audience – building a strong base of subscribers with the content he generated at (the long since retired) webmaster-resources.com. Two years later, after publishing a beginner’s web development book which was popular with that audience, the SitePoint forums were launched to a small but already engaged group who were keen to learn more about the topic. Note the timeline here – the community platform was selected, designed and launched years after Inception began.

The goal of the Inception stage is to reach what is known as “critical mass” – when more than 50% of the growth and activity is generated by community members, with the founder (or community manager) withdrawing or moving to more strategic work. The most effective way of achieving this is through the network effect created by steadily broadening reach through a concentrated group of power users.

The SitePoint community saw early success thanks to the heavy involvement of Mickiewicz, who worked tirelessly answering questions almost single-handedly in the early days. His work paid off and that initial audience became an engaged group of beta testers, with many going on to become volunteer moderators. Using this distributed approach, the values and norms which are established in these early days persist and act as the cultural foundation of the future community.

It was a highly successful strategy that pushed them quickly through Inception to the Establishment stage, also known as Growth.

Stage 2: Establishment

As more books were published, their authors were adopted into the community as subject matter experts and new subforums were added in response to demand. This measured approach to growth allowed them to properly test the community-market fit, avoiding the all too common mistake of trying to scale based on assumption. Starting small with limited subforums meant there was no paradox of choice for new members and none of the dreaded ghost towns that spring up when information architecture isn’t carefully considered.

The Establishment stage is one of exciting chaos. Community builders begin to employ more aggressive acquisition and engagement tactics to increase activity and build momentum.

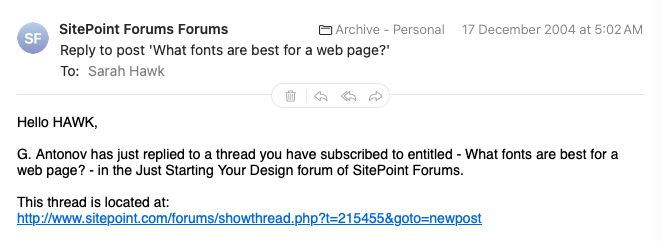

There is a transition in leadership and governance as the founder retreats and moderation moves to a crowd-sourced model, usually spearheaded by power users. It was at this stage in SitePoint’s lifecycle that I entered the picture, back in late 2004.

Subject matter experts were making their mark, with the rapidly accumulating knowledge ranking well in search results – further powering the acquisition engine which drew me in. A highly engaged team of volunteer moderators formed the backbone of the community, connecting members and amplifying voices. New subforums kept popping up, a steady stream of new members flowed in and competition was fierce for Member of the Month. The sense of community was strong and it was that which kept me going back.

The Establishment stage comes to an end when members are generating more than 90% of the activity and growth has stabilised. The community has become self-sustaining and self-governing. Cultural norms are strongly embedded and operational frameworks and processes are well established.

Stage 3: Maturity

As the community reaches maturity, the chaos calms and there is a shift to a more systematic approach to community management. Community builders can refocus – dialling back on acquisition and engagement tactics in favour of a maintenance strategy that leaves space for structured planning and the professionalising of operations.

For SitePoint, that meant hiring a Community Manager to head up the large team of 55 volunteer moderators and subject matter experts of which I’d been part. The year was 2010 and that was my introduction to the world of professional community management and the nightmare of administering vBulletin.

The team was already operating as a well oiled machine. Governance was distributed amongst Team Leaders, Advisors and Mentors assigned to different subforums; all following centralised processes which were well documented and regularly reassessed. Our work was mainly focused around member retention and maintaining the strong sense of community which was core to our strategy for managing healthy fragmentation.

Although growth had stabilised, interests were diversifying so we worked hard to ensure that groups weren’t becoming siloed. We merged and deprecated levels of subforums, we divided audiences where it made sense and split out early subgroups. Ultimately it became apparent that we were outgrowing the platform. vBulletin was no longer flexible enough to meet our changing needs.

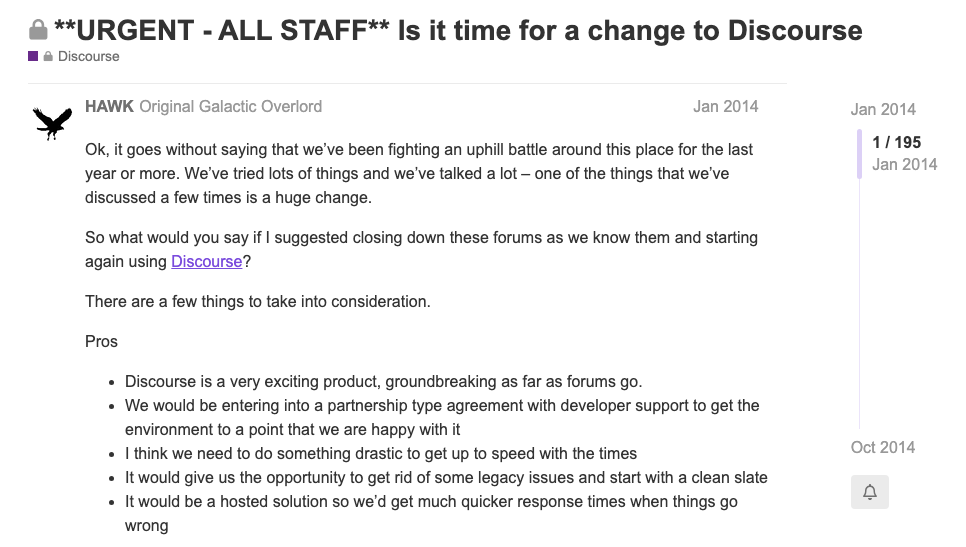

We went looking for a more scalable alternative; and I found one when Discourse entered the market in late 2013.

It was such a refreshing change. There was a lot to like, but it was Discourse’s flexible approach to scalable community building that most appealed most. Human-centric functionality (like the Trust Level system and just-in-time messaging) designed to encourage healthy online behaviour was so effective that our moderation load was more than halved, freeing up our team to concentrate on longer term strategic planning.

The Maturity stage introduces an engagement evolution, with activity patterns changing from early stage growth-driven engagement to deeper, more thoughtful interactions. All the beginner and intermediate level questions have already been asked and answered, so it is at this stage in the lifecycle that community builders should reassess their knowledge management practices. Content should be regularly pruned to keep search results accurate and information architecture should be streamlined for ease of discovery. It is also time to ensure robust policies exist to protect long-term institutional memory at scale, as the community moves to the final stage of the lifecycle.

Stage 4: Mitosis

Also known as the Legacy stage, Mitosis is a state that not all communities will reach – nor should they. Named after the biological process where a cell splits into identical child cells carrying exactly the same DNA, Mitosis happens when a community intentionally splits into smaller, focused sub-communities.

Membership is now multi-generational, with veterans, regulars, and newcomers coexisting by respecting the cultural norms that have been carried down since Inception. The content that has been generated up until this point serves as an institutional knowledge base, helping new members get up to speed quickly – in turn giving veterans space to engage more deeply. It also serves as a recorded history of norms, values, decisions and traditions – a powerful tool for supporting the retention of culture through fragmentation.

There are many ways that a community might approach splitting out self-sustaining systems which operate semi-independently. It starts organically with the natural formation of transitional zones that partially segregate cohorts, such as onboarding spaces or exclusive expert or veteran lounges. When managed intentionally, onboarding spaces with engaged mentors can act as a vehicle for assimilating new members gradually into the wider community, exposing them early to the collective value system and operational frameworks. During the later stages of the member journey, access to exclusive spaces based on a progressive reputation framework can act as a powerful retention tool, motivating experts to remain engaged.

At SitePoint we took a more proactive strategy to fragmentation, building governance systems within each subject area that enabled them to operate as individual sub-communities. This approach allowed us to scale in a way that kept experts engaged by narrowing their audience enough to keep it focused. It was a successful strategy, evidenced by the number of original staff members still operating in their volunteer roles a decade later.

Managing Growth Transitions

Recognising transition moments is fundamental to successfully managing a community through its full lifecycle. Understanding different behaviour patterns and why they happen enables community builders to strategise accordingly. For instance, there is an engagement paradox that occurs when growth stabilises and early fragmentation means that the depth of discussion varies across different spaces. The community strategy must now adapt to take into account the growing number of lurkers – members that sign up and quickly discover a depth of institutional knowledge so rich that they don’t need to ask questions. The ones that do engage have different motivations than those of new member cohorts during earlier stages of the lifecycle.

As per-capita engagement declines, meaningful connection must be reengineered and reincentivised. Without this consideration there is a risk that veteran members become disenfranchised – and it’s those members that comprise the backbone of the community.

Common Lifecycle Challenges

Stalled growth during early Inception may indicate a market-fit or conceptual issue. During Growth it is more likely to be a motivation related retention challenge. During the Maturity stage, plateaus may indicate that discoverability is being compromised by information architecture that isn’t scaling effectively. And sometimes it simply means that the community has reached the end of its lifecycle – and that’s ok, but you still need a plan.

Other challenges are phase specific. Veteran alienation can arise in later stages if longtime members start to feel displaced by shifting power dynamics. Compounded by frustration at the quality dilution that occurs if standards aren’t maintained as volume increases, those important members start to feel a shift in the perceived value of engaging – and a pattern begins that must be intentionally interrupted.

Recognising potential future challenges and having mitigation plans is excellent, but only if you have the frameworks in place and ready to go when you need them. The first line of defence is always the moderation function, so keeping those processes both stage appropriate and scalable is vital. The scalability aspect can be built into your growth strategy from Inception, but the stage appropriateness part requires time and flexibility. Make plans based on educated guesses but be prepared to pivot when you see patterns begin to change.

Sustainable Community Health Metrics

The best tool for monitoring change is data. The tricky part is defining what success looks like at different stages and working backwards to ensure you’re collecting data early enough to notice patterns that while not interesting at the time, may be the key to solving future challenges.

During the early stages when community builders decide which metrics to track, the focus is squarely on growth. What they may not take into account is that fairly quickly it will be retention stats that will demonstrate whether the community has true and lasting intrinsic value. Data on cohort engagement patterns can add important context when challenges arise later in the lifecycle and are difficult to generate retrospectively. Plan for the long term, even if you don’t know that you’ll get there.

Long-Term Sustainability Strategies

Continuity planning should include a leadership succession strategy that isn’t disruptive to the community. I have seen this handled successfully and I’ve seen what can happen when there isn’t a plan.

Planning should include modelling financial viability through the different growth stages. Understanding the basic mechanics of business planning and how to effectively engage stakeholders will become necessary skills in the later stages of the lifecycle when your growth metrics start stabilising. Advocating for the community as it evolves by uncovering and articulating new ways to define and deliver value to the business may be the only way to guarantee its future.

Learning from Legacy Communities

15+ years in this game is enough time to study the full lifecycle and I have noticed some characteristics that are always present in the communities that survive through maturity and beyond.

They collectively prioritise the work required to maintain a deep sense of identity and purpose, forming a strong backbone which makes them extremely resilient. They protect two things fiercely – their shared values and their collective history – and those things bind them tightly enough to survive through periods of great change.

Successful community builders understand the sciences of motivation and persuasion, creating frameworks that intrinsically motivate members during different stages of their journey. They form deeply loyal leadership teams that communicate well, demonstrate curiosity when it comes to problem solving, and recognise the value of working collectively.

While early decisions can sometimes have lasting impact (ahem Facebook Groups), the only things that should be set in stone are the purpose, identity and values of the community. Everything else should remain as flexible as our ability to predict the future necessitates. Communities that are adaptable and leverage change as an opportunity to evolve are more likely to thrive than those which can’t assimilate.

Legacy communities have a lesson to teach us about the importance of well structured documentation and maintaining discoverable archives. Their documented historical memory acts as a cultural artefact which long outlives the community, preserving value for future generations.

Building for the Long Term

Researching for this post was bittersweet. It reignited my love and gratitude for the SitePoint community, but I was confronted by a deeply sad truth. With the exception of meta, every community I have ever played a role in building is gone. No archives, no evidence of the thousands of hours of work, in fact, barely a trace of existence outside of a few sad 404s.

So to all the community builders out there, no matter what stage of the journey you are at – what legacy do you want to leave behind and have you got a plan for it?

It’s a long game, remember.